Part of our ongoing investigation into the Southern California rehab industry.

Philip Ganong, his wife and their 34-year-old son built a fast-growing, multimillion-dollar empire on urine.

They collected it from drug addicts at their chain of Southern California sober living homes. They created labs to test it. And they charged insurance companies to analyze it.

But the success story was a scam, according to prosecutors, who have accused the Ganongs of fraud. They say the family used a network of doctors and others to bilk insurers out of as much as $22 million for tests that were unnecessary or never performed.

The Ganongs have pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trial.

But the allegations raised in the Ganong case highlight what a growing number of critics say are chronic shortcomings in the oversight of California’s multi-billion-dollar drug rehabilitation industry.

Among the complaints:

- Drug counselors and others can run sober living homes and some types of treatment centers without passing any kind of criminal background check. Even people convicted of drug crimes are allowed, under current state law, to get a license to own and/or operate drug and alcohol rehab centers.

- Addicts and families considering rehab have no easy way to check the records of treatment centers, recovery homes or their owners or staff.

- The state lags behind others in adopting reforms to crack down on treatment center operators who exploit vulnerable addicts and focus more on profits than on effective care.

California is “the wild, wild west right now,” said Kansas Cafferty, a commissioner with the National Certification Commission for Addiction Professionals.

In a state with about 1,800 licensed recovery centers and an unknown number of unlicensed sober living homes and testing labs, Cafferty is among many who believe California needs to get better at rehab regulation.

“There (are) a lot of places committing crimes that authorities are trying to enforce, but they can’t keep up with it.”

Just following the rules

Marlies Perez, chief of the California Department of Health Care Services’ Substance Use Disorder Compliance Division, which licenses rehab treatment centers, said her agency can only do what the state Legislature allows.

She would not say whether her department needs more authority, or if it is doing a good job protecting consumers.

“We’re not going to quantify our functions,” Perez said. “Our role is to provide oversight. That is, once again, exercise the authority that we have” and work with other regulatory agencies when appropriate.

Carol Sloan, the health department’s spokesperson, said state codes list specific causes for denying a treatment center license. Reasons include prior revocation of a license and failure to comply with fire codes. Other than that, applications from would-be operators and counselors generally aren’t screened by the state.

Drug counselors in California are certified by industry-related agencies to work in recovery programs. And once certified, they’re governed by a code of conduct written by the certifying agency that could make them subject to discipline for such things as sexual misconduct or drug abuse.

But officials and critics say neither the third-party certification organizations, nor the state health services agency, are routinely notified by law enforcement or state officials when treatment center operators or their workers are convicted of crimes or disciplined for license violations.

Stalled in Sacramento

It’s not a new problem, and California legislators have fought about it for years. Still, they’ve made only halting progress in beefing up licensing standards and rehab monitoring. That’s partly because of industry lobbying, and because of fears that tighter rules will raise treatment costs or limit the number of rehab beds just when the nation’s opioid crisis is cranking up demand.

This year, State Sen. Pat Bates, R-Laguna Niguel, introduced a bill to reform the system, but it stalled in committee. Today, she describes the state’s oversight of rehab operators, sober living homes and counselors as “troubling.”

“There is significant resistance … to looking at a (rehab operator’s) background,” Bates said. “There’s a culture about giving these people a second chance.”

Still, she insists that background checks and tougher licensing requirements for counselors, employees and rehab operators are vital. “It’s something we need to pursue.”

The Ganongs – who ran sober living homes in Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego counties – could face decades in prison if found guilty of running fraudulent urine-testing operations.

Since they were charged in May, the Ganongs apparently have shut down their recovery homes, according to one of their attorneys. Phone numbers for some of their operations are disconnected.

But there are no state rules that required them to do that. And even if they are convicted and sentenced to prison, the Ganongs still could legally own sober living homes in California. There’s no law preventing it.

At least one family member already has worked in the rehab business with a drug-related criminal record.

Prosecutors say William Ganong served as corporate secretary of the family’s sober living homes and a director of one of the drug testing labs named in the county’s fraud case. In 2006 and 2008, records show, he pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors involving being under the influence of a controlled substance and driving under the influence.

This summer, when prosecutors charged William Ganong and his relatives with fraud, he faced a series of new misdemeanor charges filed in 2014 and 2015 for allegedly possessing an opium pipe, driving under the influence, speeding and giving false information to police. William Ganong could not be reached, and his attorney did not respond to interview requests.

A lawyer representing Philip Ganong, the 64-year-old family patriarch, did talk.

In what might be a statement about the general weakness of rehab regulation and oversight, Kate Corrigan indicated a key part of her client’s defense could be to cite the law itself.

“There was great effort to comply on his part,” Corrigan said.

“But it’s not an area that has a good definition of what you can do and what you cannot do.”

Who is the doctor?

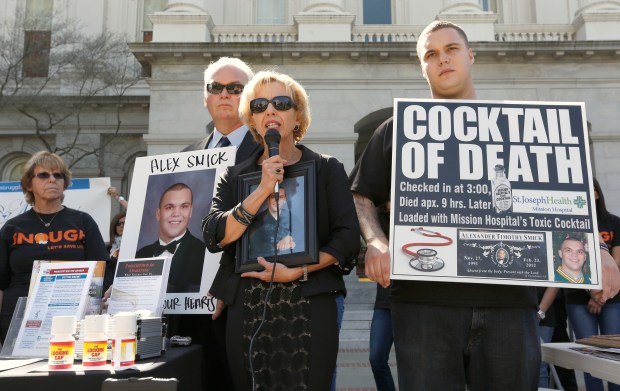

Tammy Smick lost her 20-year-old son, Alex, nearly six years ago, after he was admitted to an Orange County treatment program. The coroner’s office concluded he died of acute intoxication from the combined effects of several drugs. State records show the drugs were ordered during Alex Smick’s treatment.

Four years later, following an inquiry, investigators recommended that the state medical board discipline the doctor who ordered the drugs, Daniel Headrick. The formal accusation filed by the state attorney general’s office alleges Headrick engaged in “repeated negligent acts” in connection with the medications he ordered for Alex Smick.

Records also show a nurse was cited and fined $1,000 by a separate state agency because he was late in logging in Smick’s medication records, posting the information a half-hour after he was found dead.

Headrick denies the state’s allegations involving him, said his attorney, Raymond McMahon. The care Headrick provided was proper, McMahon added, and any issues involving Alex Smick’s treatment “relates to nursing care, not physician care.”

State officials declined to comment on the progress of Headrick’s case. Tammy Smick said the attorney general’s office and the Medical Board recently told her they have agreed to settle the case, without providing details. Potential penalties range from suspension or revocation of Headrick’s license to probation or a public reprimand, according to the accusation.

After their son’s death, the Smicks settled a malpractice lawsuit against Headrick, the terms of which weren’t disclosed.

Tammy Smick, a Downey teacher, threw herself into activism after her son’s death, retelling his story and focusing on issues such as overprescription of opioids and California’s cap on medical malpractice payouts, which she argues undercuts doctor accountability.

“Our goal is bringing awareness to medical malpractice (in) the opioid industry and detox centers,” she said.

Since Alex Smick’s death, Headrick has opened a drug treatment center, Tres Vistas Recovery in San Juan Capistrano, where he is listed as owner and medical director.

Addicts or their families considering using that rehab can learn about the state allegations involving Headrick, but only if they know where to look. In October 2016, details of the Headrick case were posted on the Medical Board of California website.

Tammy Smick believes it’s not enough. She says people considering rehab wouldn’t necessarily know to turn to the Medical Board website. She believes there should be an easier, centralized way to get official disciplinary records on rehabs, their operators and key staff.

State health officials say even when a doctor’s license is revoked, he or she can still operate a treatment center and profit from it, though they could not provide medical care to patients.

California lags other states

Smick is not the first to raise the issue of transparency. A state Senate report in 2012 found a host of oversight problems in the recovery industry, including poor monitoring of rehab centers and inadequate information sharing related to treatment center operators.

Other state officials have pointed to financial abuses in the industry that authorities say bleed millions from public and private pockets. Part of the concern is tied to so-called “junkie hunters,” people who recruit addicts from around the country and bring them to rehab centers in California in return for kickbacks.

One area of the rehab industry – sober living homes – has virtually no oversight.

The homes, where addicts often live for a few months after leaving formal rehab, aren’t required to submit any records of their operations. This is true, in part, because operators aren’t claiming to provide medical treatment and the people living in them, recovering addicts, are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The state’s findings from 2012, and a follow-up report in 2013, have sparked debate about how to regulate the industry. But that debate hasn’t prompted big change, and critics complain that California – which has about 1,800 licensed rehab centers, including more than 1,100 in Southern California – is falling behind other big states in vetting and licensing rehab centers.

“The big issue is, what do the licensure laws look like?” said Michael Cartwright, CEO of American Addiction Centers, one of the nation’s largest for-profit treatment chains. “Are they standard? Do they follow good guidelines other states follow? No, they do not.

“Time and time again, the problems get worse and worse,” Cartwright added. “Progressive states like Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey … are making serious progress.”

Some of the biggest changes are taking place in Florida.

Like California, Florida has become a hotbed of out-of-state addict recruitment and scandals related to widespread fraud and dangerous patient care. In June, Gov. Rick Scott signed a package of reforms aimed at cleaning up the industry.

The new regulations call for background screenings for all owners, directors and clinical supervisors of sober homes. They clarify laws to make kickbacks illegal and empower state regulators to make unannounced visits to sober homes. They also allow state prosecutors to use racketeering laws to crack down on patient brokering and fraud networks in the industry.

In addition, licensed treatment centers in Florida have been prohibited from referring addicts to sober living homes that have not met the standards of a voluntary, third-party certification process.

Other states are taking actions as well.

In Pennsylvania, as part of the state’s response to the opioid crisis, lawmakers authorized funding for 45 “Centers for Excellence,” treatment facilities that combine medical, behavioral and job training services for 11,000 addicts. And the governor is pushing for the state to begin regulation of sober living homes.

Coming to America

Tonmoy Sharma worked as a psychiatrist in the United Kingdom before losing his license in 2008 for allegedly dishonest and unprofessional conduct in connection with research involving patients.

He also was accused of employing titles he did not possess – “Ph.D.” and “professor” among them – and “fell significantly short of the standards to be expected of a medical practitioner undertaking medical research on human subjects,” documents from the United Kingdom show.

Sharma said he believed he had obtained proper ethics clearances when he did his research, and that his course of study was equivalent to a Ph.D. so he was justified in using the title. A spokesman said he no longer practices psychiatry.

After moving to Southern California, Sharma built a chain of drug treatment centers, Sovereign Health, with nine centers in California and four other states with 743 beds. He also has centers that treat people for mental illness.

But before starting his businesses in the United States, Sharma’s background wasn’t widely known to California regulators.

His application to run rehab centers sparked no criminal or disciplinary background check. His application to run mental health care facilities did bring scrutiny from the state’s Department of Social Services, which oversees other types of group homes, and he was allowed to operate. There is no indication that the Dept. of Social Services alerted any other state agency about Sharma’s licensing issues and other problems in the United Kingdom.

Today, Sharma and Sovereign Health are under investigation by the FBI.

In June, federal agents raided his offices and confiscated records and computers. Documents related to the FBI’s search warrant have been sealed, so the focus of the investigation is not public.

Sharma says he has done nothing wrong. He contends the FBI investigation was sparked by an ongoing legal battle he’s waging with the insurance provider Health Net.

The health care giant has accused Sharma’s company of billing fraud worth more than $33 million. Sharma has responded by accusing Health Net of improperly cutting off payments for patient care.

Separately, the Dept. of Social Services is seeking to revoke Sharma’s license to run group homes for the mentally ill over allegations that proper consent was not given to perform genetic and HIV testing on children, among other problems.

But even as he battles law enforcement, the state and at least one major insurer, Sharma is among those who argue that there is “no quality control” in the state’s rehab industry.

“You will find treatment centers in Orange County like Starbucks,” he said.

“Yesterday, a tire shop; today, a treatment center. You don’t require background checks. You don’t require any skill to do this. That’s the problem.”

Business model

Court documents accuse the Ganongs of creating a network of rehab-industry companies that fraudulently exploited the testing of addicts’ urine.

This, according to prosecutors, is how they did it:

In December 2011, Pamela Mae Ganong, now 61, of La Jolla created Ghostline Labs Inc. to submit urine testing claims to insurance carriers. The next month, Ganong hired physician Suzie Schuder to run the lab, which conducted urine tests.

Prosecutors allege some of the tests were not covered by the laboratory’s certification or were not necessary, and that Schuder received $21,884 from 2012 to 2013 to run the laboratory and write prescriptions. Schuder has pleaded not guilty to fraud. Her attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

In January 2012, Pamela Ganong, Philip Ganong, and their son, William Ganong named themselves officers of the William Mae Corp., which ran sober living homes in Orange County, Bakersfield, Los Angeles and San Diego.

The company advertised on Craigslist and word of mouth among drug users to get clients, according to a court declaration by the District Attorney’s Office.

Yet within a year the company, operating under the name Compass Rose Recovery, mushroomed from 12 employees to nearly 100. That growth sparked interest from insurance giant Anthem Blue Cross, which suspected the company’s sudden success might be a result of something more than smart business, records show.

During this period, the Ganongs also formed Compass Rose Staffing, which referred recovering addicts for temporary jobs with nonprofits. But hundreds of recovering addicts from the Ganongs’ sober living homes also were employed at the Ganongs’ various companies, and prosecutors say those workers were required to take frequent urine tests as a condition of their continued employment.

The staffing company “was just a front to facilitate the collection and testing of urine,” Pamela Angle, an Orange County District Attorney’s Office investigator, wrote in May.

Pamela Ganong and William Ganong also submitted insurance claims worth more than $1 million for testing on their own urine, Angle wrote in a court declaration. The lab charged between $400 and $1,500 for each test.

Records allege that over a three-year period the Ganongs’ urine business billed insurance carriers $22 million and collected $15 million. William and Philip Ganong recruited doctors who treated addiction and allegedly bribed those doctors into writing drug testing prescriptions, according to documents.

One physician, Carlos X. Montano of Costa Mesa, received a flat fee of $2,000 a month and $150 per prescription, prosecutors allege in court documents. Montano also is charged with fraud. His attorney, John Barnett, declined to comment on the case.

The Ganongs and other defendants are scheduled to appear in court on Feb. 13.

Staff writers Jordan Graham and Teri Sforza contributed to this article.