By Lauren Hepler | CalMatters

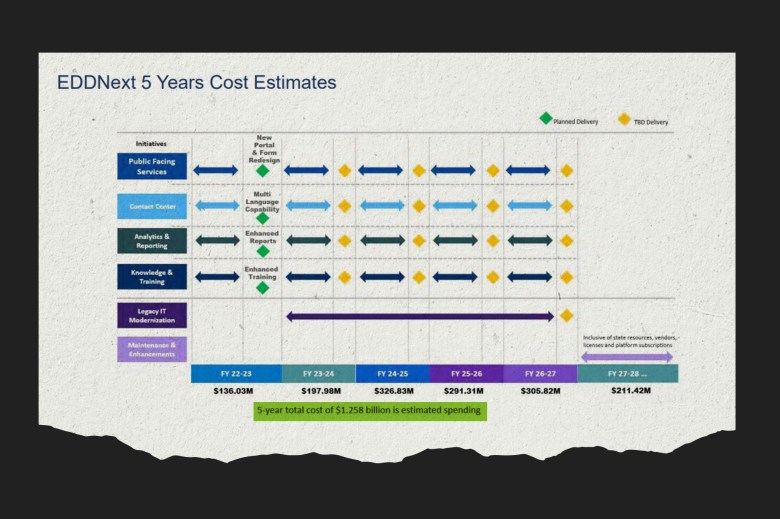

Five years, $1.2 billion. And a new model for government contracting in the tech-challenged home state of Silicon Valley.

That is what California officials say it will take to overhaul an employment safety net pushed to the brink by record pandemic job losses, widespread fraud and the political panic that followed.

The biggest-ever attempt to reform California’s Employment Development Department, known as “EDDNext,” officially started late last year. A roughly 100-person team is leading the rebuild, and is already signing multi-million-dollar contracts for Salesforce and Amazon technology, according to interviews and records requested by CalMatters.

At the same time, the EDD is quietly making plans to move on from its turbulent relationship with longtime unemployment payment contractor Bank of America. Between now and 2025, the EDD will begin rolling out new benefit debit cards, and eventually, a direct deposit payment option from a different, yet-to-be-named contractor, the agency said in a statement.

Ron Hughes, a former state technology official and consultant who came out of retirement to run EDDNext, said his team is prioritizing “the biggest pain points for the public” — online accounts, call centers, identity verification, benefit applications — as the agency tries to turn the page on an era of mass payment delays and widespread fraud.

“EDD did over 200 technology projects during the pandemic. They were basically putting out fires,” Hughes told CalMatters. “EDDNext is really a way of being proactive about it. We want to solve some of these problems, instead of just putting Band-Aids on.”

Workers still experiencing payment delays, fraud confusion and jammed phone lines are skeptical — especially since the EDD promised many similar changes after the Great Recession around 2009. Business groups, meanwhile, are sounding alarms about the state’s $19 billion in outstanding unemployment debt to the federal government. They are clashing with labor groups who want to expand jobless benefits and increase payments to keep pace with costs of living, instead of relying on fraud-prone emergency programs like those created during the pandemic — a newer version of an old fight about the scope of the safety net.

“There’s a longstanding narrative… like, ‘Look, see, this is a program that people just abuse,’” said Jenna Gerry, a senior staff attorney with the National Employment Law Project. “If people are concerned with actual fraud, then I want to look at what solves it: fundamental reform of the system.”

For Jennifer Pahlka, who co-led Gov. Gavin Newsom’s task force to triage COVID-era problems at the EDD, the challenge ahead is emblematic of difficulties that many government agencies face in adapting to the digital age. As inequality widens and risks like fraud evolve, Pahlka wrote in her book “Recoding America” that the EDD still operates with patchwork computer systems, its staff bound by an 800-page training manual and political dynamics that can leave leadership more beholden to shifting regulatory regimes than real people — fundamental issues that could still undercut EDDNext and its 10-figure budget.

“Do I know how to wave a magic wand and fix California’s unemployment insurance system? No, I don’t,” Pahlka said in an interview. “But I do know that what we’re currently doing doesn’t work, and that other states have some approaches that we should be trying out.

“Start with not burning $1 billion in a parking lot.”

EDD Director Nancy Farias has read Pahlka’s book, and the many state audits that have dissected the agency’s recurring failures. She’s well aware of the “light switch” trap, where a government agency bets it all on one, years-long tech project, then prays it all works when a switch is flipped. To try to avoid that, she and Hughes decided to break EDDNext into dozens of smaller projects through 2028.

“It leaves less room for a big failure,” Farias said. It will only come together, the former labor union executive added, with parallel efforts to simplify the process and alleviate strain on staff: “You can have the best IT in the world, but if you don’t change your policies and procedures, it does not matter.”

The COVID hangover

This past summer, San Diego jewelry maker Phaedra Huebner found herself stuck in a loop that might sound familiar to people who filed for unemployment early in the pandemic.

At 8 a.m. each day, Huebner, 52, said she dialed the EDD right as call centers opened to ask where her benefits were. She used a trick she learned on YouTube to bypass pre-recorded messages, punched in her Social Security Number and tried to get in the queue to talk with a real person. Then came the redialing up to 67 times a day, bouncing between departments and, more often than not, hanging up without answers about when she might see the money she needed to make rent.

The twist: Huebner wasn’t filing for unemployment, but for disability — hinting at how issues with call centers and identity verification continue to ripple across EDD’s multiple large programs. After each day on the phone, Huebner said she wrapped her hands in ice packs to ease the shooting pains in her hands and arms that put her out of work in the first place.

“For six weeks I should have been resting,” Huebner said in early September. “Instead, I’m in pain with no disability income doing all of my own administrative work.”

The EDD’s benefit programs have always been complex and highly individualized. In the majority of cases, the EDD told CalMatters in a statement, people applying for benefits do not encounter major delays. The agency cited its own 2022 survey of several thousand people using its benefit systems, where 69% reported they were “completely or mostly satisfied” with the unemployment application process, and 63% were satisfied with the disability process.

The problem, workers and attorneys say, is that even a portion of the EDD’s customer base amounts to tens of thousands of people — and when things go wrong, they can still go very wrong.

In January 2022, for instance, the EDD froze 345,000 disability accounts, including an unknown number of legitimate ones, amid a wave of suspected fraud involving claims tied to fake doctors. Putting stronger safeguards in place is one of the “lessons learned from the pandemic that we should be applying to every program,” said former California State Auditor Elaine Howle.

“People saw the (unemployment) program was being defrauded left and right,” Howle said, “and it was like, ‘Shoot, if I can do that, what other programs are out there that I can defraud?’”

Mason Wilder, research manager of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, said unemployment and disability programs are just two examples of many public and private sector systems being targeted as online fraud gets easier. It now costs as little as 25 cents to buy a Social Security number online, leading to a cycle of large-scale attacks followed by broad fraud crackdowns.

The risk of unsuspecting people getting caught in dragnets is only anticipated to grow, Wilder and other analysts say, as technologies such as artificial intelligence allow scammers to work faster and more easily forge documents. Benefit debit cards used by California’s CalFresh food assistance and CalWorks cash aid programs have also been targeted in recent fraud schemes, along with many similar programs across the country.

“It becomes kind of whack-a-mole,” Wilder said.

That’s not to say that the EDD’s pandemic unemployment problems have been neatly resolved. As of September, more than 130,000 California workers were still fighting long unemployment appeals cases, waiting an average of 137 days for a hearing with a state administrative judge, according to U.S. Labor Department data analyzed by CalMatters.

The EDD’s own data shows that the number of rejected unemployment claims has climbed steadily since the pandemic surge, to more than 1.9 million claims rejected from March 2020 through October 2023. The agency says that reflects the success of anti-fraud measures; advocates see it as evidence that the state also continues to trap legitimate workers, given that federal data shows EDD decisions are overturned almost half of the time on appeal.

“I definitely don’t think anything’s been resolved,” said George Warner, director of the Wage Protection Program at Legal Aid at Work. “A lot of the issues remain the same.”

The EDD stresses that it has implemented changes recommended by the California state auditor — including providing more public data and creating a new plan for future recessions — but the auditor remains unconvinced that several major issues have been remedied. This past summer, the auditor added the EDD to its list of “high-risk” state agencies, unlocking additional resources for potential future audits. Top concerns were poor customer service, high rates of benefit denials overturned on appeal and the agency’s inability to tally pandemic fraud, delaying the state’s two most recent annual financial reports.

“EDD’s mismanagement of the (unemployment) program has resulted in a substantial risk of serious detriment to the state and its residents,” the auditor’s latest report concluded.

EDD Director Farias said that all states face similar challenges, especially when it comes to quantifying fraud that is widely varied and, for obvious reasons, difficult to trace.

“There is no definition of what is fraud… and that’s really the biggest problem,” said Farias, who also sits on the board of the National Association of State Workforce Agencies. “There is Nigerian fraud ring fraud — Fraud with a capital ‘F’ — and then there is, you know, Mary Jo Smith down the street that really didn’t understand what the program was.”

In San Diego, Huebner unexpectedly got an up-close look at how identity verification issues continue to plague the EDD. After she filed for disability, it took a month and a half to get her first check. But then she received a letter in the mail addressed to a woman with a different name and employer in Northern California, which said that her benefits had been discontinued.

When Huebner tried to call to figure out what was going on, she realized that her YouTube trick to get through on the phone no longer worked, throwing her back in benefit limbo while she recovered from a spinal procedure and waited to see if a new EDD debit card showed up.

“They won’t tell you anything,” Huebner said in late October. “Pain is one thing, but helplessness is totally different.”

What next for California unemployment reform?

Before he was hired to fix the state’s pandemic problem-child, EDDNext director Hughes was enjoying retirement on his Sierra foothills ranch dotted with cattle, horses and sheep. He put that on hold and went back to work at the EDD when his former colleague Farias asked him to.

Hughes is quick to note that he wasn’t there for the worst of the pandemic issues. He spends a lot of time talking with other state tech executives who can empathize, such as peers at the DMV.

Even from the outside, it wasn’t hard to see what went wrong at the EDD during the pandemic.

“When you roll out a solution, it needs to work. If it doesn’t work and they call the help desk, you need to answer the phone,” Hughes said. “We didn’t do either of those things very well.”

In June, his team launched a new online portal called “MyEDD,” which uses Salesforce technology for workers to file and track the status of their benefits. Some users reported crashes during the first days of the rollout, but the system stabilized. It will be built out over time, Hughes said, as the agency works through contracts for identity verification and a “claims navigator” to show workers all benefits they are eligible for.

A new call center system using Amazon technology is slated to debut within the year — first for the state’s older disability system at the end of 2023, Hughes said, then for unemployment next summer. The idea is to ultimately go from the five or six systems that EDD agents currently juggle to one system for processing claims.

“Under the new system, there is a single pane of glass,” Hughes said. “As soon as they call in, all the information on their claim will come up.”

It’s not the first time the EDD has tried to streamline its claims system, parts of which date back to the 1980s. Pahlka in her book compares making sense of the patchwork programs to going on an archaeological dig.

After the Great Recession, the state paid Deloitte to upgrade several facets of its operation, including part of its claim management systems, in a series of contracts that ballooned to more than $152 million from 2010 to 2018, copies provided to CalMatters show. That system was one of several that state reports later found buckled during COVID, but Deloitte was awarded another $118 million as the state doled out emergency pandemic funds, according to contracts provided to CalMatters.

The irony, as Pahlka observed in her book, is that the money went to the very vendor “which built the ineffectual systems in the first place.”

U.S. Rep. Katie Porter, a Democrat from Orange County who sits on a U.S. House Oversight Committee that has investigated pandemic unemployment fraud, sighed heavily when asked about the past Deloitte “unemployment modernization” project — a response, she said, to both the contractor in question and a broader lack of oversight on big-budget projects.

“Deloitte has an unfortunate track record of not getting it done here,” Porter said. “If we’re going to contract this and spend our dollars with a private company to do this, we have to hold them accountable for delivering.”

Deloitte defended its work for the EDD in a statement, noting that “many technology constraints highlighted by California elected officials during the pandemic related to functions in EDD systems that Deloitte was not contracted to maintain.”

The company declined to comment on whether it intends to bid on the new EDDNext project.

Hughes said that no vendor is off the table for EDDNext, but that past contract performance will be taken into consideration for all bidders. This time around, Hughes said the plan is structured to include more oversight.

“It’s just way too much work for one vendor to do, and so we’ve split that up,” he said. “We’ve got different vendors doing different solutions. We can manage them much more effectively that way.”

Familiar fights

Another promise of EDDNext, Farias said, is that workers, advocates and front-line staff will have more of a say in how the project is built. The agency has also created a new customer experience arm, which outside observers like Pahlka see as a promising development.

Gerry of the National Employment Law Project was among the worker advocates briefly shown a version of the new EDD online portal before it launched. It will require more sustained effort, she said, to ensure that people relying on the system end up with something easier to use.

“It’s hard, because yes, we see certain incremental changes, but these systemic issues are still there,” Gerry said. “Unless there really is a big overhaul within the agency culture and the way they’re approaching this EDDNext project, we’re going to see these problems continue.”

The EDD maintains that more visible changes are coming, including a planned redesign of the agency’s 10 most-used forms to cut unnecessary questions, translate them into more languages, and make them easier to understand and access online.

Similar efforts are also underway in many other states, where officials have raised questions about whether the federal government should do more to standardize applications, anti-fraud measures or other elements of the system. Robert Asaro-Angelo, commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, recently told a U.S. House committee that states and territories that all currently have their own processes could use more guidance to bolster security while ensuring rightful benefits are paid.

“We keep talking as if there’s one unemployment system. There’s 53 different systems,” Asaro-Angelo said. “These fraudsters being able to pick and choose — they couldn’t be happier.”

In California, concerns about the nuts and bolts of the state’s unemployment program are magnified by a more fundamental concern: the financial quicksand beneath the entire system.

The state unemployment fund that pays for benefits is operating in the red, or “structurally insolvent,” as the California Legislative Analyst’s Office put it in a July 2023 report.

Though the state was making progress on paying down its $20 billion-plus pandemic unemployment loan from the federal government, state forecasts now show the debt creeping back up, adding urgency to a fight over whether to change California’s 1980s-era tax system.

Business groups are already pushing Gov. Gavin Newsom to use other state money to pay down the debt, despite California’s current budget deficit. The state has spent more than $680 million in recent years to pay interest on the federal loan.

“California’s vast unemployment insurance system has been under enormous strain since 2020, and employers are paying the price,” the California Chamber of Commerce argued in an August report.

From her vantage point at Sacramento’s Center for Workers’ Rights, labor lawyer Daniela Urban has watched cycles like this play out before. When the economy tanks, everyone — stressed-out workers, angry lawmakers, state watchdogs, the governor — wants to know what’s happening at the EDD.

But as people go back to work, the outside interest and funding wanes: a collective failure to fix the system before the next time things go south.

“Once the watchful eye is gone, I worry that it will be neglected,” Urban said, “and not by the people working there.”